‘they changed their skin’

a new series by Daisy Billowes

this is my new series: they changed their skin. a group of paintings about mythological women that looks at their metamorphosis as agency. a moment they stop being symbols and start being authors within their new selves, between what was imposed, and what they choose to become. there is so much in my head with these paintings I don’t want the internet to devour it into its black troubled algorithmic hole but instead give it some space to breathe. so here we are.

transformation is not just a shapeshift thing. this series is not about scales and monsters and all that mythology textbook business, but instead reflects on a deeply human act of introspection. these women are characters drawn from Greek mythology, and this act of ‘transformation’ has almost always been written as punishment, not liberation. they changed their skin reframes that. it’s about women who took what was done ‘to’ them, and metabolised it into growth.

what’s interesting about myth is that it’s like this ancient operating system for our psychology. it has been rebooted more times than you can shake a stick. it’s a meta-language– a language used to describe another language. an inherited algorithm that decodes what it means to survive, to evolve, to make sense of pain. transformation is both spectacle and necessity. it’s public, performative, and sometimes grotesquely consumed. but for these women– Medusa, Daphne, Arachne, Psyche, Circe– in this series, it’s something quieter. something done in private, in the margins, and we’re stumbling upon them.

what’s crucial here is the voice that speaks about them. the narrator. the unseen chorus. each title in this series is not a caption, but a whisper from that collective voice that always knows a little more than it should. like the fates, the narrator already knows how the story ends, but still watches it unfold with the terrible patience of history. it’s the same in Greek theatre. the chorus stands just outside the action; commenting, lamenting, warning. that’s what these titles are doing. they’re the retelling that shifts each time the myth is spoken aloud. it’s also what painting does in a way, as it re-narrates, or translates maybe. it changes the story in the act of telling. so when you read ‘her fingers eeked out shoots’ or ‘but her opinion did not sway’, you’re not just hearing the myth but instead you’re hearing the echo of its retelling. you, the viewer, become the next narrator.

firstly, Medusa. Ovid technically has a version where she was once a mortal priestess, and after Posidon set his sights on her Athena transformed her hair into snakes. but there are other stories that join her just as a gorgon. but regardless, we all know her as the one with snakes for hair. her head was cut off by Perseus and given to Athena as a prize (lucky her). we are often presented with only Medusa’s head in a lot of art and references, which suggests the main thing about Medusa was that she was ‘conquered’, her head a trophy (and a warning). remember that her gaze could turn people into stone? of course a punishment, but somehow also a twisted protection? there is a wonderful photograph by Cindy Sherman here that became a bit of a focal point for me when researching her. comical in nature, colours muted (almost stone like) she’s not screaming, or in a performative rage. she’s full bodied, and although hinting at a sexualised version of herself, i enjoyed the silliness of it, her ownership of it.

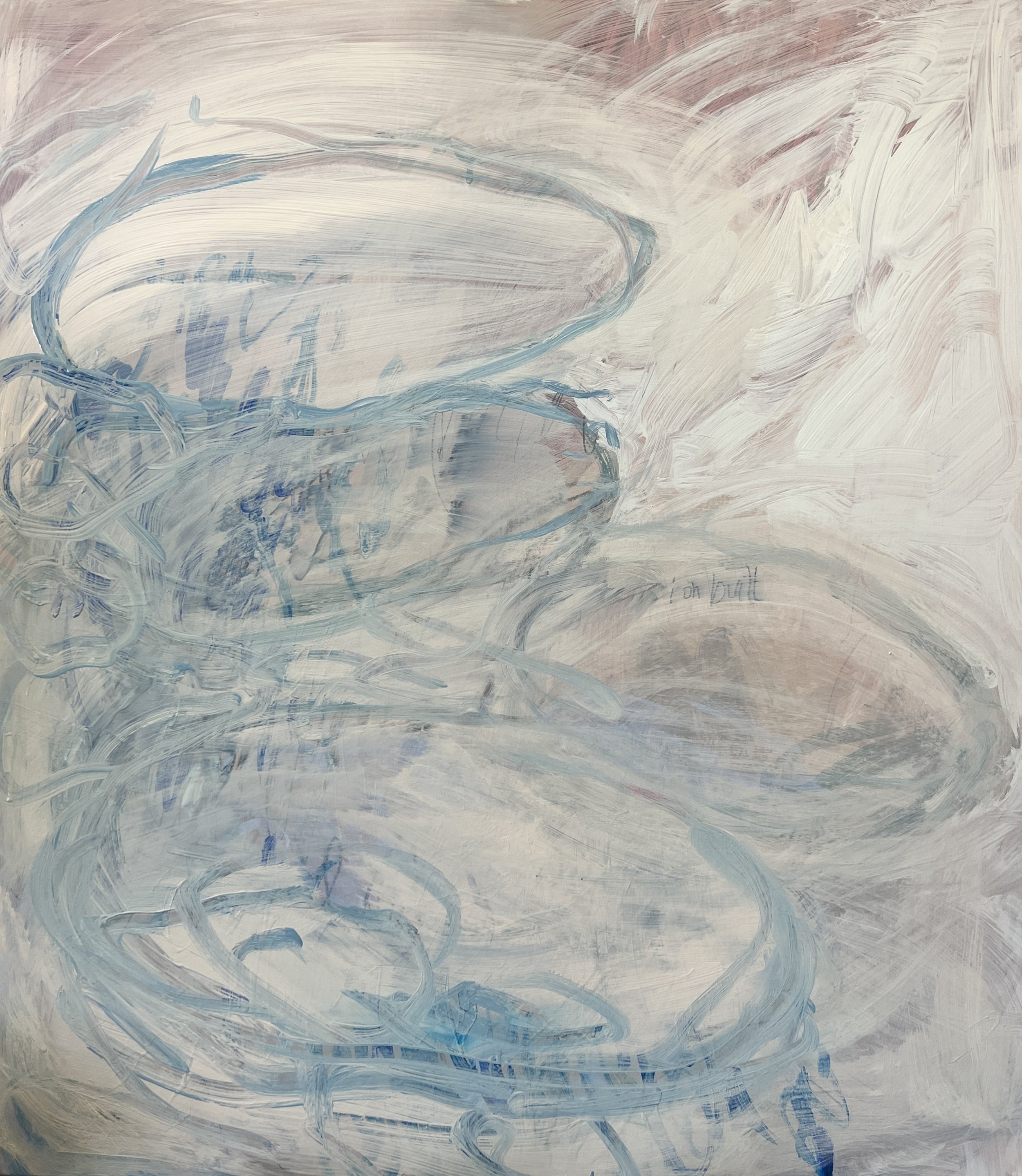

(above: ‘ownership in full’)

i wanted the muted, stoney colours in ‘ownership in full’, the purples (which can be seen as the colour of female independence), the hair to be there but not the focus. i have tried to keep as much energy in these pieces as possible, a whirlwind of feeling. written scrawl that shows frustration, but not in a vengeful, raging sense. i am what i am, full in body. i’ve turned away from representing the female body in strict form as i wanted his series to be about introspection and self-acceptance– ownership, even.

Daphne’s story is one long chase scene: Apollo pursuing, Daphne fleeing, body turning to bark mid-flight. she becomes a laurel tree, referenced in ‘laurel spread on her head– a victorious crown’. which is actually where we get laurel for a victor’s crown from.

(above: ‘laurel spread on her head— a victorious crown’)

i relate this a little bit in the context of women in the public eye. celebrated, then consumed, then immortalised (good or bad). a never ending vicious cycle. Daphne would rather be a tree than be ‘consumed’ by a man, although she did not technically ask to be a tree, she just wanted to escape (she asked her river-god-dad to help out).

in ‘her fingers eeked out shoots’ her hands are still pink, still human, her transformation not yet complete. the paint drips, like sap, but also blood, an earthyness to being alive that she is still processing.

(above: ‘her fingers eeked out shoots’)

Daphne here didn’t win by loving, she won by leaving. taken by the landscape, these references i’m making focus on the prickly nature of the outcome (with the scraggedy scribbles). the pencil marks are like veins and branches, and note the slightly longer ‘s’ to emphasise this in ‘her fingers eeked out shoots’. the composition and structure from both ‘laurel spread on her head’ and ‘but her opinion did not sway’ are from Bernini’s ‘Apollo and Daphne’. rooted in the trunk at the base, with an upward tree growth from centre left to top right, the energy is there, but not the female body.

(above: ‘but her opinion did not sway’)

instead of this divine feminine body about to be eaten up by the earth, she is instead here a tree with whispers. a nod to some fleshy undertones, but it is about her inner consciousness instead. the pencil marks make that clear. it feels sensory knowing the thin pencil lines are a whisper in the trees.

next, Arachne. a woman who was being punished for something she was incredibly good at (and knowing it). something any woman who’s been told she’s intimidating will understand. she challenges Athena to a weaving contest, wins, and is turned into a spider. nobody beats Athena. the works around Arachne stem from Bruce Conner’s Arachne from 1959. although incredibly different in a material sense, it was the tights stretched thin, forming fragile webs that really stuck with me. it’s feminine craft turned trap. ‘the tension built’ is a direct reference to those tights in Conner’s work. light pink layered over the darker hues and scribbles. the small hit of the itchy pencil making its way through the painted layers you can just about make out the word ‘built’ from the title.

(above: ‘the tension built’)

the painted circles become loops of thought, obsession, thread, labour. ‘she had tied herself into knots’, although a play on words, it’s also a signal to her uneasy thoughts. she has defied a god!

(above: ‘she had tied herself into knots’)

you can see the weaving patterns in the orange and blue pencil. i particularly like the knotty orange lines at the base of the painting, images being unravelled. keeping the colours light and serene reflect that (what some would call) mundane but feminine activity of weaving. i’ve pushed the activity here from left to right– a signal also to the way you weave. likewise, ‘her skills outsmarted her’ are along the same vein.

(above: ‘her skills outsmarted her’)

there’s more frustration here, more circular motion and the piece feels more awkward. she has a new body, a new fate. the deeper blue pencil was brought in to signify more melancholy than ‘she tied herself into knots’ and the square-ishness pulls back to the awkward and uncomfortable feeling. a thought process we are witnessing in depth, more so than a ‘dear diary’ moment. not something that you can easily describe. i like to think of her weaving these lines and texts from chaos into pattern.

as a mid-series breath, i have included ‘flowers for the rebirth, we are told’. it’s a visual exhale as it’s not about a specific female figure. it nods to Evelyn De Morgan’s ‘Night and Sleep’ in both form and meaning.

it’s about the beauty of pause, a quiet collapse. the poppies dropping downwards are opiate and offering (a symbol of a sleeping draught from Victorian times). i’ve used it as a symbol of death and renewal combined. night and sleep are spreading a rebirth to these women in the series. a reminder that these aren’t surrenders, but instead a reset. a reminder that transformation requires these sorts of interludes.

(above: ‘flowers for the rebirth, we are told’)

i have kept the transition here from top to bottom. dark into light as the poppies are scattered. the hum of brighter light at the base suggests a cycle of descent and emergence. the foot in the far right of the painting is the only significant ‘absolute’ body part that i have drawn in this series. it’s one of the only solid things we know– death and rebirth.

we move on to Psyche. in a nutshell, she is an incredibly beautiful woman who marries Eros (the OG Cupid). at the beginning she can never physically ‘see’ Eros but disobeys the order and takes a sneaky peek at him with an oil lamp. when she does see him, she suffers a series of divine endurance tests before becoming immortal herself. in these two smaller pieces Psyche is done with performance. myth is often romanticised (and this is one with a happy ending, actually) but i’m focusing on her anger pre-enlightenment. ‘eros can go fuck himself’ is a hint to Eros’s invisibility and Psyche’s frustration whilst undergoing her mammoth tasks. also a comical nod to Eros being the god of love, desire and a little bit of fuckery.

(above: ‘eros can go fuck himself', she thought’)

there are tiny layers of a transparent yellow oil paint over the deep greens which you can catch in a certain light– the yellow oil from the lamp as Psyche catches a glimpse of the god she is married to. both body and absence, both soul and lust (or curiosity). the green hues in both ‘eros can go fuck himself’ and ‘the friendly reed guided her’ are her raging around the earth trying to make sense of what she is caught up in.

(above: ‘the friendly reed guided her’)

a nod as well to the absurdity that a reed (yes, the plant) helped her in one of her quests. the smaller scale of these two is a nod to her still being mortal, smaller than anything divine that she is yet to make sense of. she is trapped in these little spaces with little room to breathe.

the star of the show, in my opinion, is this larger scale work of Circe. a witch who lives alone and turns men into pigs. she is banished to her own island for using witchcraft, and refines solitude into sovereignty. it feels radical– the idea that a woman can be happy alone, and it needed space.

(above: ‘from a choice of mortal or divine’)

‘from a choice of mortal or divine’ was constructed to show her island floating in the almost square frame. the island glows as a theatre of isolation where animals are scattered, men only remembered as shapes. the pencil marks are contained within the island, a marking of her territory, a containment of frustration, command, and acceptance of solitude. there are small animal creatures in the bottom left, again marking her territory with her witchcraft, and a symbol of anyone who dares enter her personal space. the writing ‘from a choice of mortal or divine’ is a reference to Madeline Miller’s novel ‘Circe’. it’s a choice she makes to become mortal rather than remain divine. for mortals can be just as wicked as the gods, but their fragility, imperfections, and finite existence give more meaning to what it means to be alive. the energy in this piece, to me, speaks volumes. there is room in this canvas to play more freely with what is calm and what is chaotic. your own body can experience this as much as your eyes, getting swept up in the playful, descriptive marks. so many juicy bits to enjoy it reads almost like a play in itself.

what all these women share is the refusal to stay as they were written. their transformations aren’t cinematic; they’re messy, private, deeply human. these works strip that narrative back to its raw bone. their skins change, not as punishment, but as adaption. each painting becomes a document of emotional evolution: quiet refusals, sharpened edges, and drips that dry into pattern. they changed their skin isn’t about beautification or transcendence. it’s about the messy rewiring of identity that happens when you’re forced to adapt, and somehow end up stronger, stranger, and truer for it. myth feels less ancient than ever. it’s the same story, just in new skin.